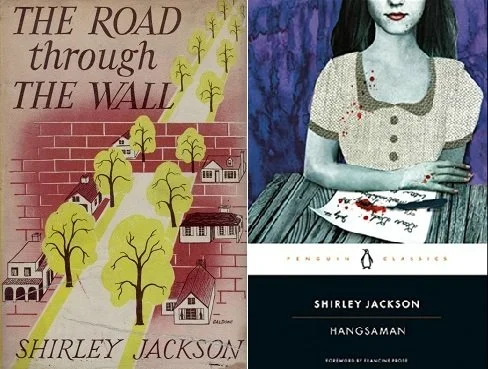

I got on a Shirley Jackson kick late in 2025 and decided to read her novels in the order in which they were published. I finished the first two, The Road Through the Wall and Hangsaman, in a row, but other things drew my attention during The Bird’s Nest and so I’ve put it aside for now (not for want of its quality; I’m sure I’ll revisit it later). I’m combining the first two in one entry as I don’t have a ton to say about them individually.

Jackson’s prose is polished from the start, and there is no awkward phrasing or self-conscious overwriting common to new novelists, particularly those writing “literary fiction.” The writing is excellent, but the stories are not yet as strong as they will become. Jackson is, at her core, a short story writer, and in these early books, she doesn’t seem to have fully mastered a lengthier form (something she would ultimately do to tremendous effect with The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle). Though enigmatic and far from action-packed pulps, those latter works showed a flow and rhythm that suited their length. Her first two, by contrast, can feel formless at times.

The Road Through the Wall feels the least “Jacksonian” of the bunch, which makes sense given it was an early work. the voice is deft and laconic as ever, the dialogue demonstrating the clipped niceties and hostile undercurrents that would become a common thread, but the structure and subject matter are unlike her later works. It isn’t set in New England, for one, but in a sunny California suburb, where it chronicles the lives of half a dozen households, most of Which contain working families with young to teenage children. There is no clear protagonists, and the jumble of names can be hard to keep track of. Not a great deal happens until a sudden and shocking act of violence in the final pages, which feels largely like a contrivance of literary fiction at the time than something authentic to the story.

Hangsaman feels more like vintage Jackson. Common themes emerge here that would find homes in her later novels and stories: the mousey and troubled young woman, the cozy superficial camaraderie of women that betrays sharp angles beneath, the petty theft and intrusion on personal space. There is also a surreal fatalism from the book’s college age protagonist Natalie, which would find a much more impactful resolution in Hill House, The Lottery, and some of her other short stories.

These are still good books and worth reading for those who intend to explore Jackson’s broader body of work. But her final two novels reign supreme. It is a shame she died as young as she did, as all signs point to a writer who was continuing to hone her craft.